Endangered Species

Sec 7 Programmatic Biological Opinion

LIST OF ENDANGERED SPECIES FOUND IN SOUTH DAKOTA →

SECTION 7 OF THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT (FWS)

2016 Listed Species State and Federal

USFWS SPECIES PROFILE →Most roadway and stream crossing projects do not impact the American Burying Beetle; however, some projects in Gregory, Tripp, and Todd Counties may affect this species. Impacts to this species are minimized by reducing the project footprint to the minimum practical. Impacts to riparian habitat should be avoided.

Eagles are usually associated with dominant or co-dominant trees in both the nesting and wintering periods. The vast majority of bald eagle nests can be found within one-half mile of water and are rarely located greater than two miles from water. Nests, constructed primarily of sticks with other material added for lining, are almost exclusively found in live trees. Wintering sites consist of very large perch trees that are usually located near open water or in close proximity to other available prey items.

Bald Eagles have nested in Gregory, Brown, Yankton, Bon Homme, Spink, Charles Mix, Union, Robert, Sanborn, Hutchinson, Bennett, Lyman, Marshall, Clay, Minnehaha, Hughes, and Meade Counties in SD. The bald eagle winters regularly in large numbers along the Missouri River from Pierre to Yankton and in scattered locations across the state.

Construction projects located within a half mile of active bald eagle nests may have special provisions to reduce impact or disturbance to the nesting eagles.

USFWS Species Profile →

The northern long-eared bat is a medium-sized bat about 3 to 3.7 inches in length but with a wingspan of 9 to 10 inches. As its name suggests, this bat is distinguished by its long ears, particularly as compared to other bats in its genus, Myotis, which are actually bats noted for their small ears (Myotis means mouse-eared). The northern long-eared bat is found across much of the eastern and north central United States and all Canadian provinces from the Atlantic coast west to the southern Northwest Territories and eastern British Columbia. The species’ range includes 37 states. White-nose syndrome, a fungal disease known to affect bats, is currently the predominant threat to this bat, especially throughout the Northeast where the species has declined by up to 99 percent from pre-white-nose syndrome levels at many hibernation sites. Although the disease has not yet spread throughout the northern long-eared bat’s entire range (white-nose syndrome is currently found in at least 25 of 37 states where the northern long-eared bat occurs), it continues to spread. Experts expect that where it spreads, it will have the same impact as seen in the Northeast.

The species historical range included Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming.

Projects that include tree or structure removal may affect this species. Impacts to this species are minimized by seasonal work restrictions.

USFWS SPECIES PROFILE →

South Dakota Topeka shiner Range Map

Special Provisions for Construction in Topeka Shiner Inhabited Streams

SOUTH DAKOTA TOPEKA SHINER MANAGEMENT PLAN (GFP) →

Annual Monitoring Reports

2021 Report2019 Report

2018 Report

Whooping Cranes breed and nest along lake margins or among rushes and sedges in marshes and meadows. The water in these wetlands is anywhere from 8 to 10 inches to as much as 18 inches deep. Many of the ponds have border growths of bulrushes and cattails, which occasionally cover entire bays and arms of the larger lakes. Nesting has also been reported on muskrat houses and on damp prairie sites. Whooping Cranes prefer sites with minimal human disturbance. Wetlands provide the Whooping Crane with protection from terrestrial predators.

Whooping Cranes tolerate very little human disturbance, especially during nesting, brood rearing, and during flightless molt (May to mid-August). Slight human disturbance is often sufficient to cause adults to desert nests. On wintering grounds, Whooping Cranes will tolerate human disturbance if it is not associated with obvious threats.

USFWS Species Profile and Map →

© 2026 State of South Dakota. All Rights Reserved.

Becker-Hansen Building

700 E. Broadway Ave.

Pierre, SD 57501

Modern Logic

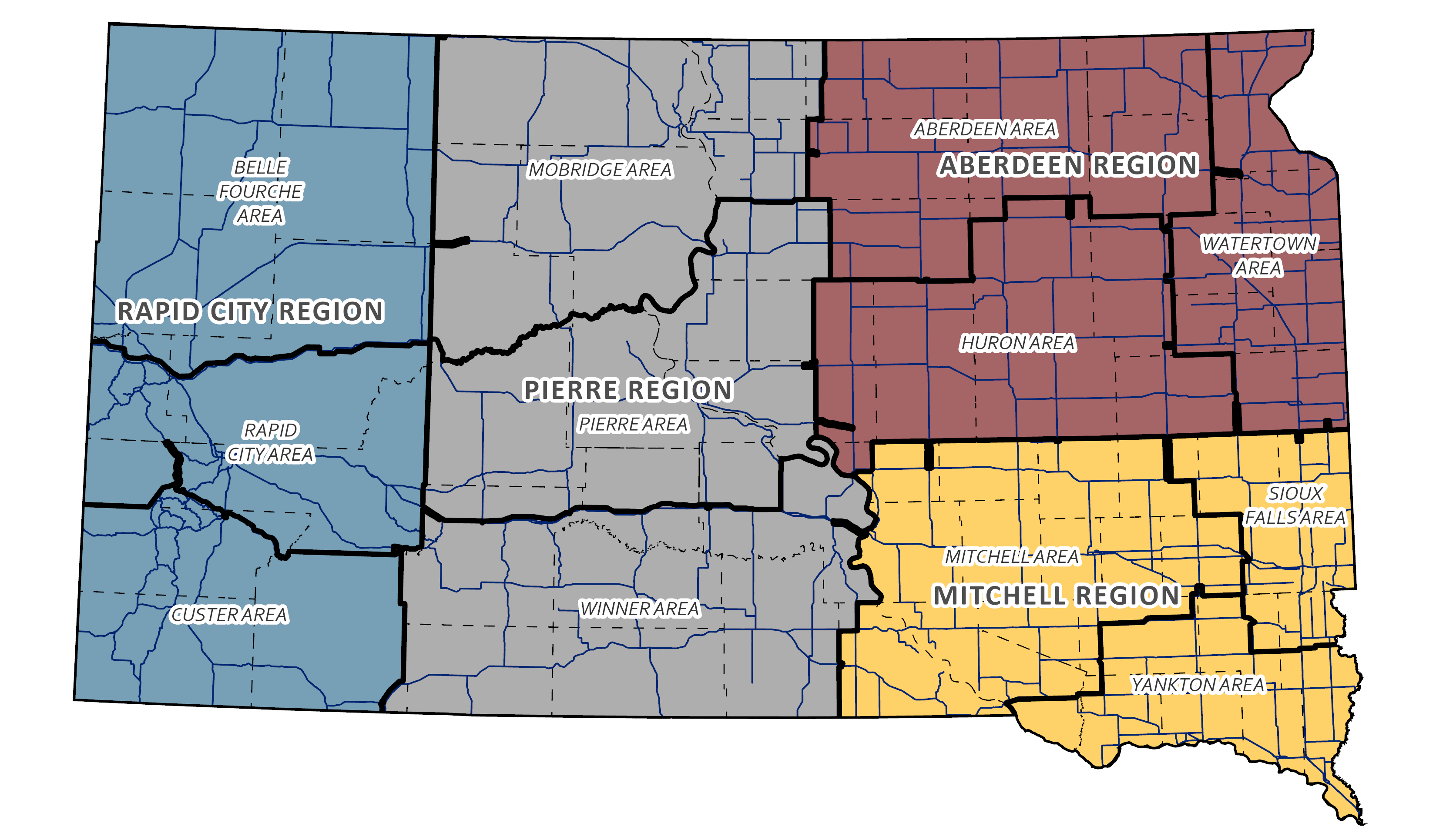

Region & Area Offices

Travelers

© 2026 State of South Dakota. All Rights Reserved.

Becker-Hansen Building

700 E. Broadway Ave.

Pierre, SD 57501

Modern Logic